Before there was Goop and #proffee, there was root beer. However irrelevant it seems now, claiming approximately 0.003% of the global market share of carbonated soft drinks while remaining all but unknown outside of the United States, this indigenous elixir-turned poor man’s Dr. Pepper effectively paved the way for the big business of liquid diabetes we know today. And it all began in the name of good health.

Since time prehistoric, indigenous people of eastern forests of North America would drink boiled roots and berries to manage a host of afflictions, from rheumatism to gout. British conquistador and conspirator Walter Raleigh, who learned of the practice in 1585 during his nation’s first failed attempt to claim the Americas, brought sassafras and other “cordials” back to Briton to sell as miraculous health tonics.

Three centuries later, as the Temperance Movement swept through the United States,

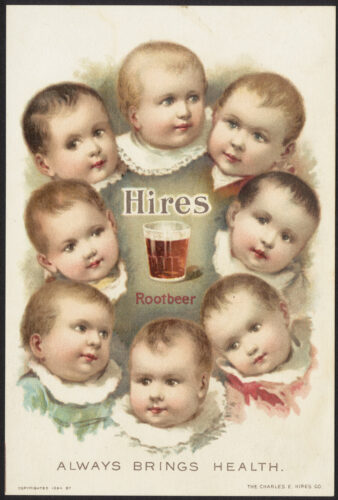

teetotaling druggist Charles Hires would “invent” an alcohol-free tea culled from the woodlands of his native New Jersey. Combining between 16 and 26 powdered ingredients, from sassafras to wintergreen, Hires first marketed his blend to health-conscious homebrewers.

Looking to appeal to stalwart, tea-averse miners at the purported urging of Temple University’s founding President, Hires rechristened his beverage root “beer” while leaning on recent bottling innovations to increase access for all. This combined with Hires’ marketing moxie—wherein he claimed that his drink could cure everything from tuberculosis to cancer—quickly made the upstart pharmacist a millionaire.

Before the end of the century, however, myriad competitors had emerged to get their own slice of the Temperance pie, from Emile A. Zatarain, Sr. to Edward Barq. By 1886, morphine addict and ex-confederate soldier John Pemberton also joined the party, dealcoholizing his “French Wine Coca” to give birth to what he called “a most wonderful invigorator of sexual organs,” otherwise known as Coca-Cola.

The success of these entrepreneurs didn’t go entirely unchecked, of course. For three years, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union locked Hires in litigation until he could prove that his new “beer” was indeed alcohol-free. Meanwhile in the south, unfounded racist outrage preempted Coca-Cola to go cocaine-free in 1903, just three years before Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act to establish federal labeling requirements while attempting to handcuff snakeoil-style marketing claims.

It wasn’t until 1960 when the FDA would ban unprocessed sassafras—a natural building block of the drug MDMA—under the largely unsubstantiated grounds that it was a carcinogen. In the same year, Hires’ family sold the late founder’s company to the first in a line of culinary conglomerates; its current overlord, Keurig Dr. Pepper, remains tight-lipped as to whether Hires even remains in production at all.

Now straddling the gray area between “natural” and “artificial” flavors, such soft drinks instead lean on the addictive and fleetingly euphoric effects of upwards of 40 grams of sugar per can, a proven source of the many ailments it once claimed to have cured.

Worth $221.6 billion globally as of 2020, the carbonated soft drink industry continues to thrive at the expense of its consumers, but the market indicates an ever-growing thirst for healthier options. In an era when the global wellness industry is currently valued at $4.4 trillion and TikTok health trends practically dominate the discourse, perhaps things are starting to come full circle. Next stop, New Jersey woodlands?